The town was once derided as Cesky Crumbling, but today it can truly be described as a Czech charmer whose homes that can date back to the 15th century have been beautifully restored.

Ancient eyes seem to follow you wherever you go. No they’re not spies left over from the Communist era. They’re decorative faces painted on the upper floors of houses in Cesky Krumlov that, like most everything in this remarkable town, have endured for hundreds of years.

A guided tour to the magical town two hours from the Danube is a complimentary day-long shore excursion on a Danube cruise of AmaWaterways’ newly christened AmaLea. It’s a rare treat because the place is so intact from its antiquity that the entire town has been declared a Unesco World Heritage site.

We’ve followed the Moldau River–or in Czech, the Vlatava River–for two hours by bus from Linz, Austria, to reach the castle and town that began to develop on a hairpin bend in the river in the 13th century.

Cesky Krumlov literally means Bohemian Krumlov (to differentiate it from another Czech town named Krumlov in Moravia to the southeast). But once you’ve visited it, there’s no mistaking it for anywhere else. Its narrow, rambling cobble-stone streets are lined with sturdy stone buildings. Many are decorated with trompe-l’oeil, including faux windows that seem to have Renaissance inhabitants peeking out of them, now doubt awed by the throngs of daily visitors that now come to see them.

The layout of streets that radiate out from a central square was dictated by the geography of the town’s location on a horseshoe-shaped curve in the Vlatava.

Cesky Krumlov had already developed into a thriving market place when Bohemian king Emperor Rudolf II bought it in 1602 and rich homes of burgers and traders were built as it became the seat of power of Austrian financiers, the House of Eggenberg.

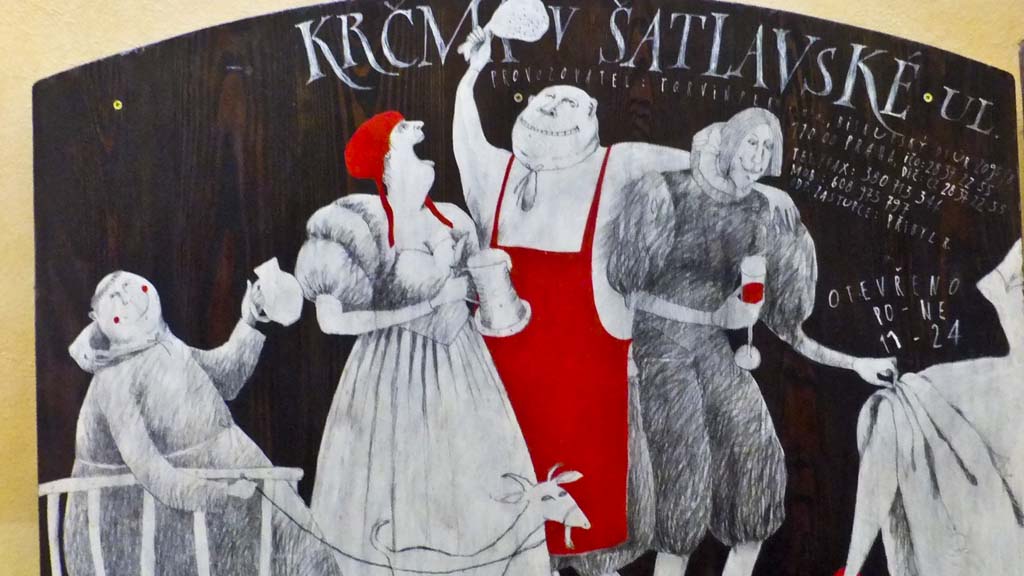

That made is a financial center and a place of elegant taste. Not only does art seem to be everywhere, it’s impossible to escape the temptation of the local Eggenbeerg beer. The town also became a religious center with monasteries of several orders built around the 15th century St. Vitus Church, dedicated to St. Vitus—who became the patron saint of dancers and entertainers.

The town remained important well into the 19th century as it remained the home of the influential Schwarzenberg family. But history wasn’t kind to the town that was too far from Prague to have powerful political defenders and too lacking in local wealth to keep up elaborate homes as wars and then Communism swept through this part of Europe.

Our guide insists that as recently as the 1970s, it was possible to buy a home in Cesky Krumlov for the equivalent of only a few hundred dollars. Of course, that came with the responsibility of maintaining a building that may have seen pigeons rather than people living in the upper floors. Now, the town has gained a cachet and new owners have meticulously restored most of the buildings to near their original conditions.

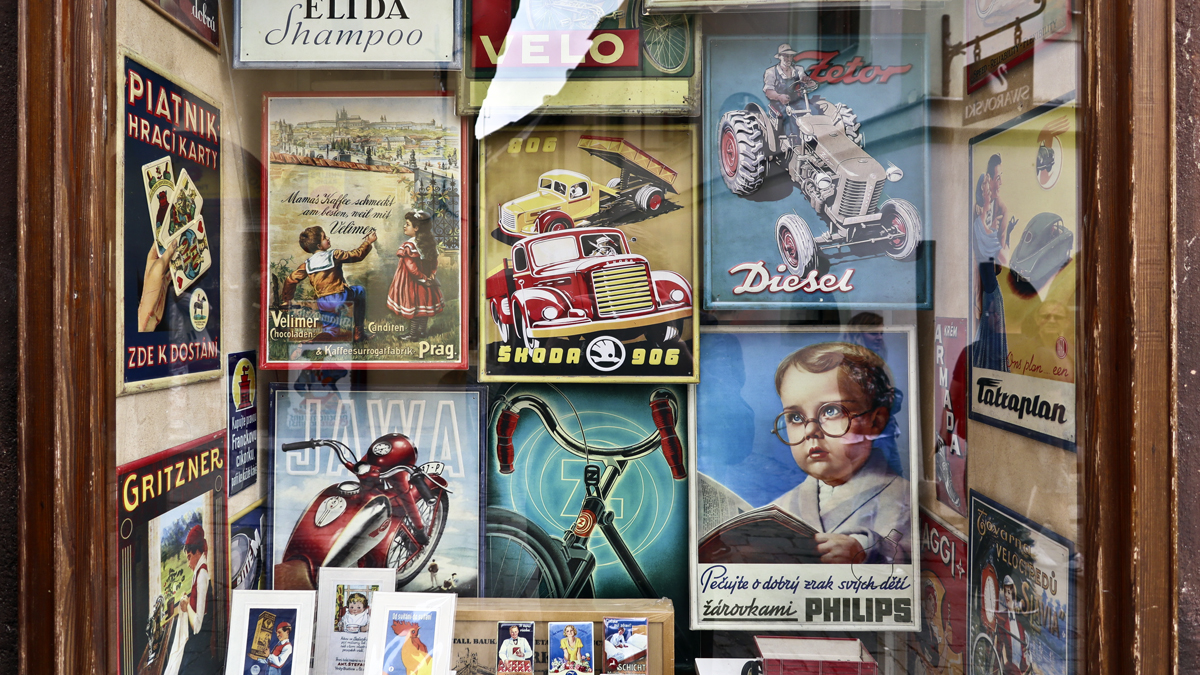

Fortunately, many of the interiors with their carved beamed ceilings were intact enough to be completely restored and ornate doorways and windows are now functional again. This has once again become a town of shops, many of them selling handicrafts and antiques. Many stores specialize in carved wood and puppets. There are also innumerable stores selling new and old signs and drinking paraphernalia from a dizzying number of Czech breweries.

And there are plenty of local art galleries that seem to prominently display cheeky art of nudes and slightly surreal scenes. That might be in part due to the fact that one of the area’s heroes is the Austrian artist Egon Schiele, known for his intense and sensuous studies of the human form, whose mother was from Cesky Krumlov.

The soaring castle on the hill that defended the town was originally Gothic in style, but it’s had many additions and renovations over the centuries as fashions changed. The dominating round tower was later decorated in high Baroque, with acres of colorful murals of knights, nobles and cherubs. Getting up close became an exercise in stair climbing and standing in the courtyards and viewing from the ramparts I could see why the castle was able to ward off any usurpers with its thick walls and strategic views down over the river and the town.

Getting a look inside the restored interiors of the castle remains difficult because spaces are so small and fragile that the masses of tourists who now visit would overwhelm them. But there are ways.

A small group of us were determined to tour the castle’s completely intact Baroque theater, which is only open to small groups at a hefty admission price. Our tour guide phoned ahead and made reservations for us but there was a slight catch, the tour that afternoon was given only in Czech. That wasn’t a problem, because even though I couldn’t understand the descriptions, it was quite clear why this perfectly restored theater is unique.

You’ve seen the Baroque candle-lit interior of the castle’s grand theater in scenes from the movie Amadeus and seeing it in reality is even more stunning. The stage itself appears to be incredibly deep thanks to the scenery scrims on either side that draw the viewers’ eyes into the distance. The theater built in the 1760s has its original seating, rows of benches on the main floor for the paying guests and an ornate prince’s box with padded arm chairs for the nobility.

Our Czech guide takes us under the stage that’s rigged with ropes and winches and pulleys to change scenes and raise and lower effects that can range from angels soaring overhead to fires and storms emerging from beneath the stage. The preservation is phenomenal and there are 13 original scenes still intact, along with over 500 costumes.

But the restoration didn’t come easily; it started in the 1960s and it was 40 years before the stage was again ready for performances. In fact, renovations are continuing because modern engineers are still unsure how some of the original stage machinery works. We came away from the tour in awe of the ingenuity and grandeur of the decoration of the wonderfully intact theater.

It was a long day of walking over cobble-stoned streets and it was time for a welcome break for a local brew before making the two-hour return to the AmaLea in Linz. (In the days of Communism the trip might take five hours or more waiting for clearance at Czech and Austrian border checkpoints. The bleak border stations have now been renovated into boutiques and casinos.)

Sitting in a low-ceilinged pub near the Pivovar Eggenberg Brewery we could toast the day we’d had in another era and joy that the newly awakened and beautiful Cesky Krumlov thrives in the modern age.