Soaring hemlock trees block out our view of the sun. There’s moss hanging so heavily on the Sitka spruce trees that they seem to bend from the weight. Beneath the tree canopy, shrubs and wild flowers spring abundantly out of a seemingly thick layer of soil.

Now flash back a couple of centuries ago. Where we’re standing was covered with 100 feet of solid ice. Alaska’s vast Mendenhall Glacier has retreated so rapidly that only 100 years ago, this valley was a field of bare rock, which I wouldn’t imagine would be capable of nurturing a thriving forest.

But nature–as we’re about to discover–abhors a vacuum. I won’t get into a discussion of global warming in this story, but a visit to the glacial fjords is a remarkable demonstration of how what we take for granted today can change in just a generation or two.

I’m part of a remarkable trek arranged through Oceania Cruises from the newly renovated Oceania Regatta through part of the Tongass National Forest on our port stop in Juneau, Alaska’s capital.

There are unique advantages to touring from a ship this small. Few ships would have been able to provide such small groups with such an intensive focus as Regatta, which carries only 680 guests. Many of my fellow passengers opted for alternative tours to view whales, or eagles but I was intrigued by the opportunity to trek through the wilderness to a glacier. Only a dozen passengers have signed on for the hike and Oceania has provided two guides, so we get to go in groups of seven and get a very personalized tour.

My group is led by Lance, a gung-ho local high school teacher and football coach who spends his summers as a tour guide. And as it turns out, he’s an expert on the local flora and fauna.

As we drive out of town, we chalk up dozens of sighting of eagles, including fledglings sitting on tree stumps along the road waiting patiently for fish to swim by in glacier-fed streams.

Bear Xing warns a sign at the parking area for the forest trek and we get a safety briefing that’s short and to the point: Don’t panic. Just stop and let the guide negotiate with the bear. The forest is like a private garden for a bear and you scare them if you walk into their path. But if you’re not threatening them, they won’t be threatening in return and will let you walk away. At least that’s the way it has always worked for the guides in the past.

And so we’re off on the East Trail, over a path of broken rock but a relatively easy climb. I was wearing hiking boots but a lot of the walkers were just dressed in sneakers. Fortunately the day was dry, and the trail is well trodden, and no one had a problem. It helps to have a bit of conditioning, though, as the walk covers more than about four miles.

Experiential teacher that he is, Lance has us stop every once in a while along the trail and be completely quiet for a minute to savor the remarkable silence of the forest. And it gave us opportunities to scan the steep hillsides with their deep green vegetation.

Yes, this all was bare, solid rock not more than a couple of generations ago, but thanks to a formula nicknamed MASH, grey rock turns to green forest quickly here. M is for moss, which grows abundantly over rock and provides enough base for small shrubs like Alder to take root.

Next up is fast-growing Sitka spruce whose needles fall and add to the base of organic material over the rock. That creates enough of a base for tall Hemlock trees to set root. Of course in Alaska’s ubiquitous wind storms entire hillsides can be blown over because the thin soil provides tenuous hold for tree roots, but that just creates a layer of wood that decomposes and makes for a thicker foundation for the next generation of trees.

And they grow incredibly fast. I’m in awe of how tall and lush everything grows here. Even though the winters are brutal, summers are magical in Alaska.

Among the remarkable plants we see all around are devil’s clubs, whose broad leaves are studded with thorns that can administer nasty puncture wounds if you touch them.

s used as a native healing remedy.s claw salve handy rubbed it on the injury before their son was taken to a hospital to be checked out. Nothing was broken and the swelling had gone away by the following Monday. With an eye to caution, though Lance suggested to his player that he take it easy for a couple of weeks.

The herbal remedy sold locally as a salve and I picked some up from a Juneau pharmacy before I got back on Regatta.

Now where, you ask, is the glacier? It’s coming into view, and that’s another lesson in change.

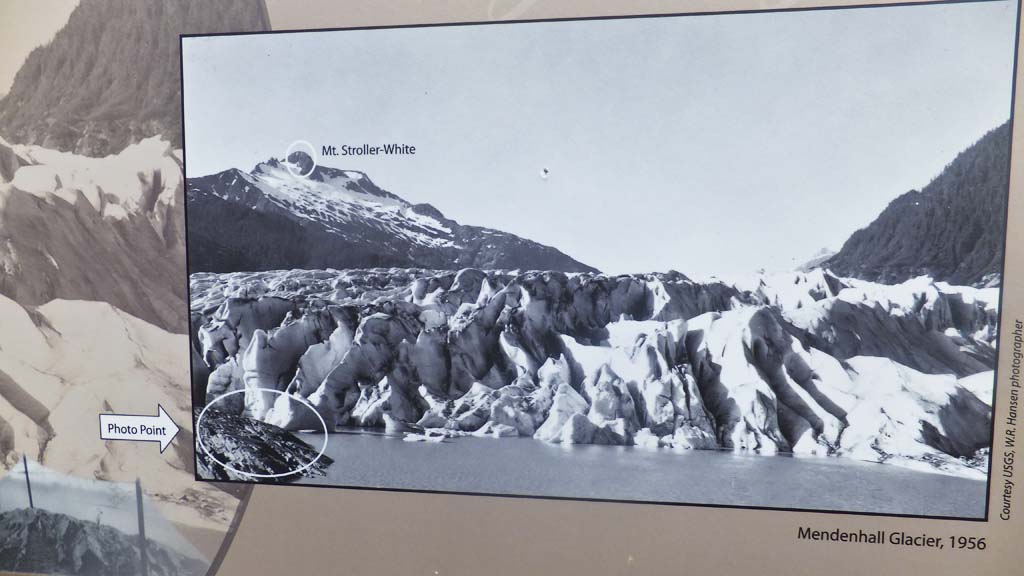

We arrive at the scenic lookout, built at the face of the glacier in 1956. Graphic historic photos at the site attest to the fact that at that time in the 50s the glacier was so close that ice soared above the viewing platform.

Today, 60 years later, you need binoculars to see the same kind of detail in the glacier from here. Its face is about half a mile away.

But that retreat has also created a stunning waterfall alongside the glacier.

My only regret is that we don’t have time to actually trek onto the ice itself.

Instead, we have to head back to Juneau to rejoin Regatta, and leave the bears to enjoy their glacial garden in peace.