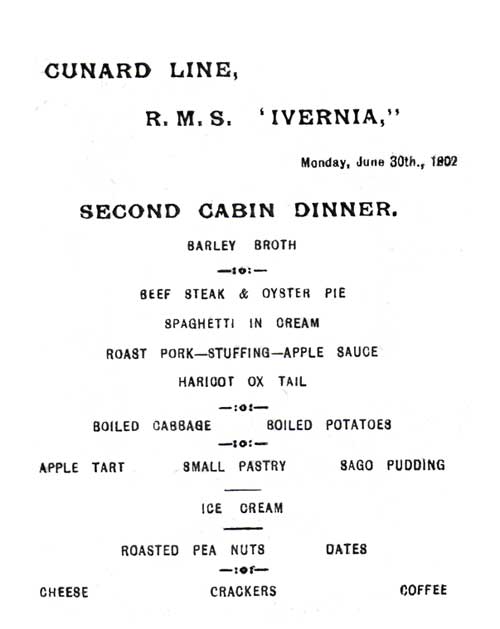

Modern cruise ships are adding restaurants that compete with the best on land. But there was a time when shipboard meals were feedings announced with a chime and you’d better be at the table on time or you might have to wait hours for the next meal. Between-meal snacks might be limited to a bowl of beef bouillon and croutons on deck.

In the days that are often called the “golden era” of ocean travel–the first half of the twentieth century–dining was a necessity, but not necessarily a gourmet experience. There were fewer options for dining and less choice on menus than in later decades. Meal times were more regimented and dress codes were invariably formal. On the grand ships, there was likely to be a live orchestra and dancing between courses, though.

A dip into the nostalgia vault of historic photos and menus suggests things are actually more golden today, and it’s a fascinating look at how tastes have changed.

The recipes are to be found in a slim but fascinating book: Favourite Recipes from The Captain’s Table, Delicious Meals from the Golden Age of Ocean Travel compiled by Simon Haseltine and printed by J. Salmon Ltd. in Sevenoaks, Kent.

So may I take your order?

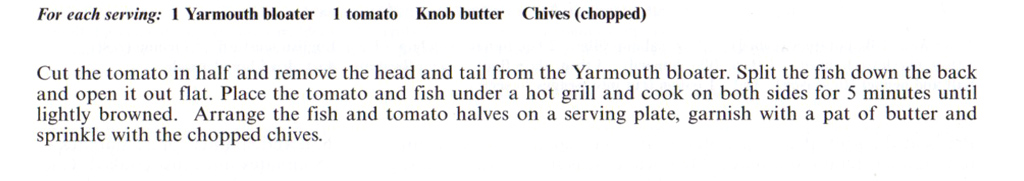

Breakfast: Yarmouth Bloaters

White Star Line, 1914

Have bloaters ever been in vogue? They showed up on many cruise menus before the First World War. They’re a type of herring caught in the waters around Nova Scotia and dried. They became known not for Yarmouth, N.S. but the town of Great Yarmouth, England, where they were served for breakfast filled with tomato and grilled, causing them to “bloat.” They’re described as salted and lightly smoked, without having been gutted, “the results retain a slightly gamey flavour.”

Other choices on the breakfast menu a century ago were grilled ox kidneys with bacon and soda scones with marmalade.

Detail from Vincent van Gogh’s Bloaters on a Piece of Yellow Paper, 1889

Lunch: Lentils a la Bretonne

RMS Queen Mary, Cunard Line, 1946

Yes, there were vegetarian dishes on menus even 70 years ago, although this recipe does depend on chicken broth. Of course, Cunard was famous for having so many chefs in its galleys that the maitre‘d in First Class restaurants would ask guests at lunch time what they’d like the kitchen to make them for dinner.

Dessert: Champagne Jelly

RMS Mauretania, British Cunard Line, 1907

The procedure is simple: pour perfectly good Champagne into gelatin, add raspberries and whip it into a thick mousse. It’s described as being “perfect for a summer dessert after an eight course meal.” Later generations have learned that Champagne doesn’t need to lose its fizz and the berries didn’t really have to be encased in a chewy gel to be perfect after a meal.

Cocktail time: Anchovy hors d’oeuvres

SS City of Rome, Inman Line, 1900

Another blast from a bygone century is anchovies on toast. This recipe is described as “a perfect way to mingle with fellow passengers while savoring a posh nibble.” The salty snack was also destined to entice you to order another round at the bar.

Dinner appetizer: Crevette cocktail

Compagnie de Navigation Paquet, 1955

Shrimp cocktail, a classic recipe from the post-war era that was probably in every suburban kitchen’s menu file for serving at the Christmas party. Paquet Line is history, but shrimp cocktail is still a cruise ship classic.

Dinner entrée: Filet of Sole with lobster butter

SS Aleutian, Alaska Steamship Co., 1935

Most of the fish we call Dover Sole are actually caught off the coasts of Alaska. It’s technically a flounder, but who’s going to be picky if it comes straight from the sea on an Alaska cruise and served with melted butter that’s been flavored with crushed lobster shells (and carefully strained we hope)? Also note the original recipe for shoestring potatoes–baked, not fried, and presumably very tasty.

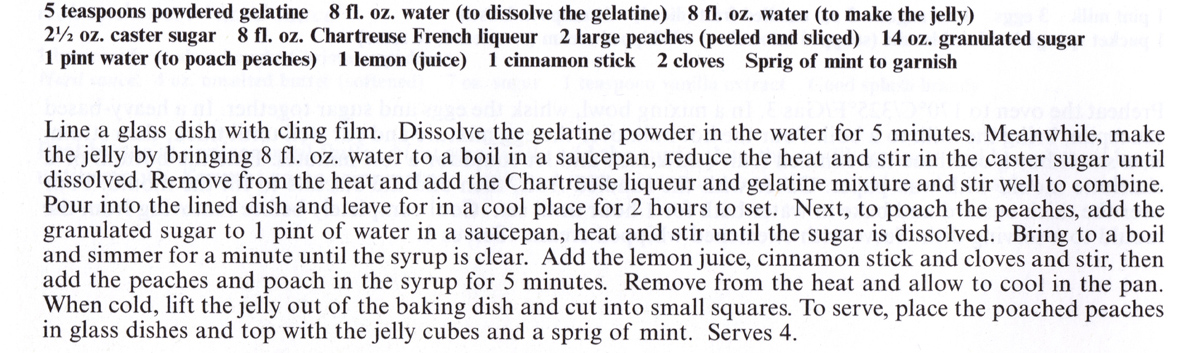

Evening dessert: Peaches in Chartreuse jelly

Titanic, White Star Line, 1912

Presumably this was being served just about the time the ship met the iceberg. We haven’t got a whole lot of feedback on how it went down with the guests.

Bon appetit!

Our thanks to Cruisington Times reader Oliver Bertin for the story idea.