A World Cruise for $10 a day!

Sounds incredible but it was true—at the dawn of modern cruising 90 years ago.

Europe was finally pulling itself back together from the devastation of the War to End Wars and the stock market was soaring to unheard-of values.

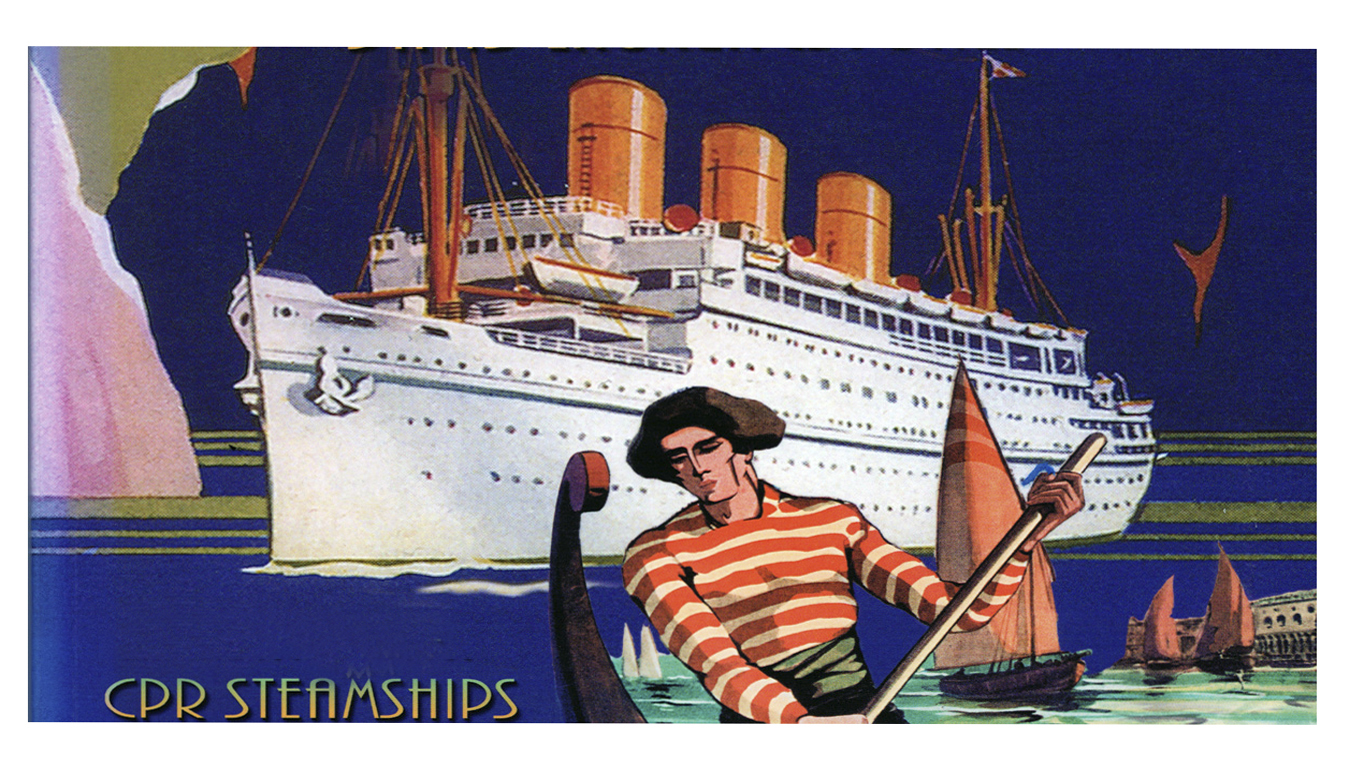

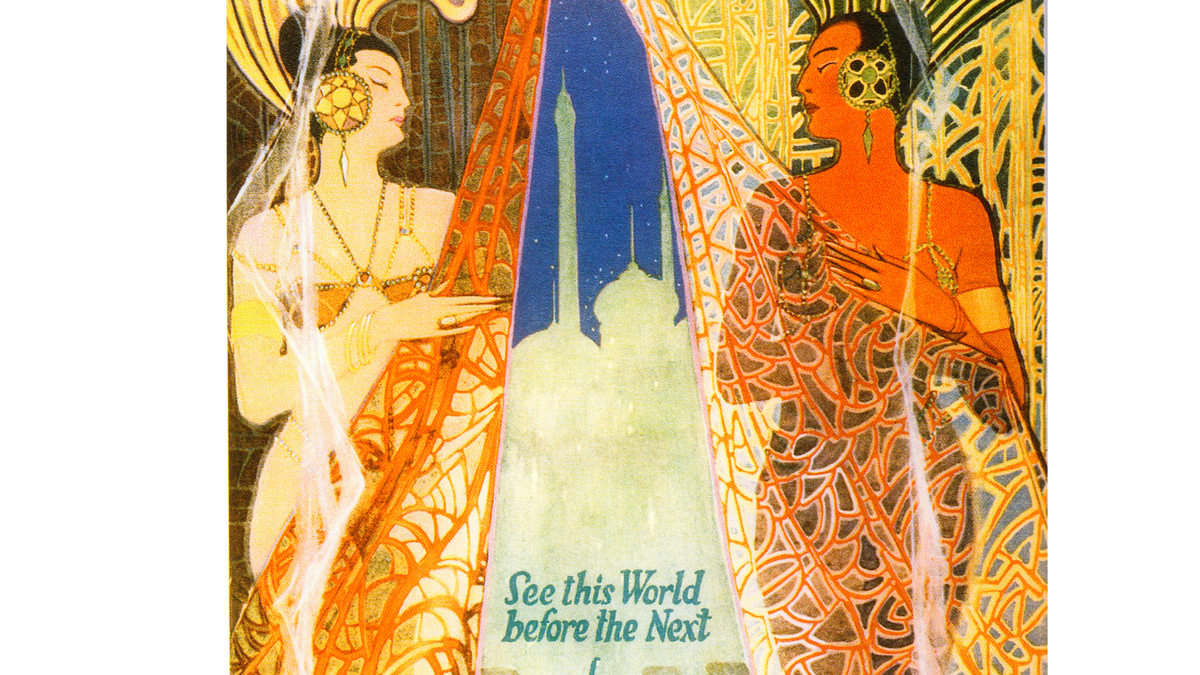

Meanwhile, shipping companies had a lot of their liners laid up in the winter months when people preferred not to brave crossing the North Atlantic. They started offering extended journeys to the Caribbean, South America and even all the way around the globe.

And the exotic voyages seem like the bargains of all time if you look at the ads of nearly a century ago. But let’s do a reality check, shall we?

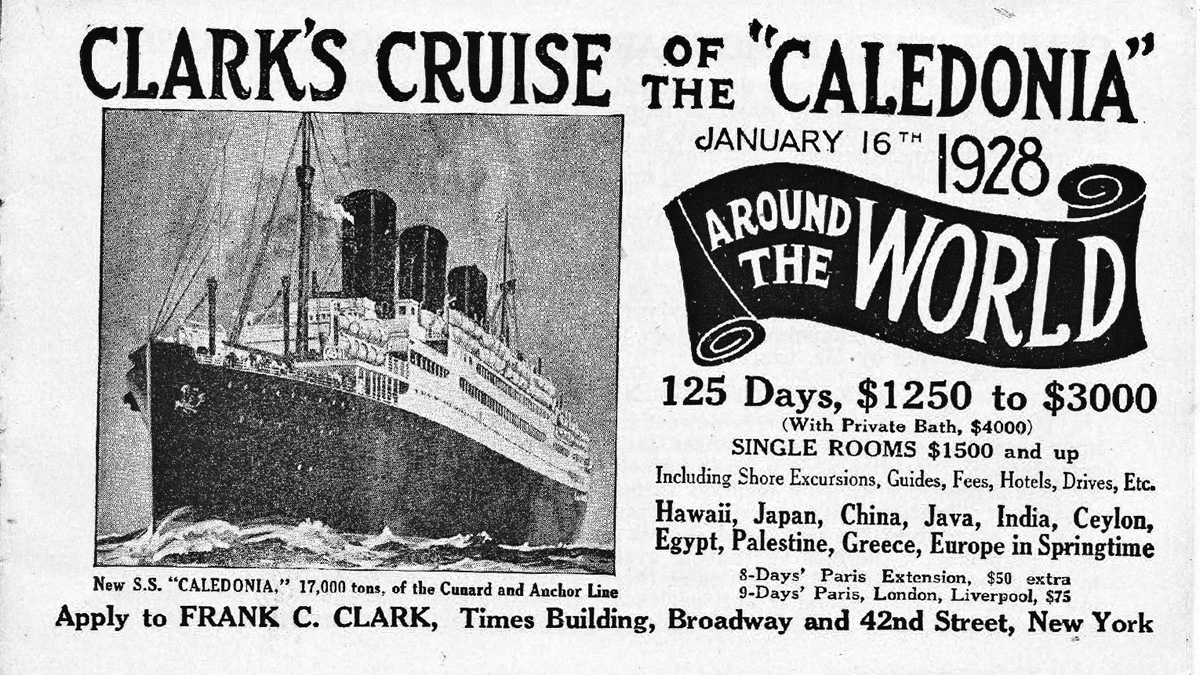

That $10-a-day was the lead-in price for a 125-day world circuit organized by Clark’s Famous Cruises of New York on the Cunard-Anchor Line oil-burner S.S. Caledonia. At the time, a good annual salary for a union or starting professional position was about the same as the $1,250 cost of that cruise in a third- class cabin.

To figure out how the value of money has changed with inflation over the years, the price back then should be multiplied by 32.5. That means $10 a day works out to the modern equivalent of $325 a day or a fare of $40,600 per guest for the whole circuit, including shore excursions, hotels, guides and fees.

Still, not bad, but consider the experience you’d have compared to today.

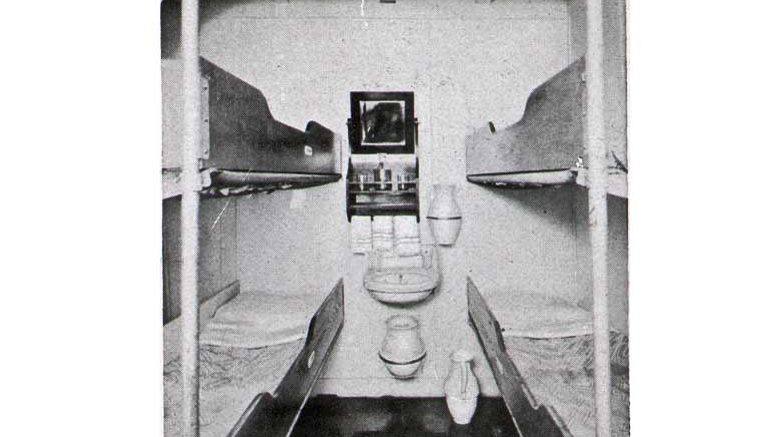

Ships have improved significantly. In the 1920s, there was no such thing as a balcony cabin and the furniture in third class might consist of railway-style upper and lower berths and little else. In first class, there might be twin beds, a sofa and a couple of wicker chairs.

An ad for United States Line from 1927 boasts that all cabins on its S.S .President Harding featured sinks with hot and cold running water.

That’s more convenience than on the 1,400 passenger S.S. Caledonia (sister ship to the SS Transylvania), built in Glasgow in 1925, which had washrooms down the hall. The only cabins on the ship with private baths were in first class and started at $4,000, or the equivalent today of $130,000 per guest.

That’s the price to sail today in palatial style suite aboard Insignia, on Oceania Cruises’ 2017 Round the World in 180 days cruise. In a promotion offered to Canadians, the USD$319,656 brochure rate for the owner’s suite was reduced to $124,999 or about USD$695 a day per guest. The brochure rate per guest for an inside is $137,384 but the promotional fare was lowered to $39,999 per guest—or USD$222 a day.

Now let’s look at how the cruise experience has improved.

Guests on today’s cruises have the run of the ship no matter what they’ve paid, but that wasn’t the case in the Roaring Twenties.

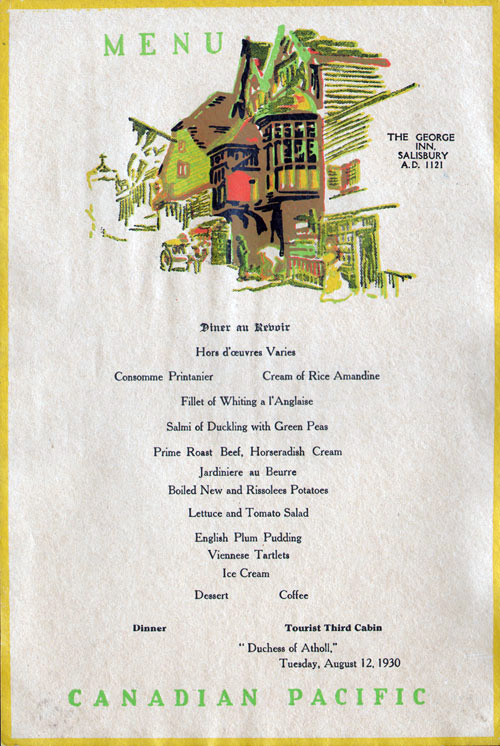

The 1927 Cunard Rule Book for Crew instructed the steward’s staff to treat third class passengers with “every civility and consideration.” And it ordered that every effort should be made to serve the diverse nationalities their ethnic food. But entire decks were reserved only for first class passengers.

The French Line advertised that “any voyager may travel third class and still be able to experience luxurious comfort and the keen delights of deck sports and other exceptional advantages—all within their ability to pay.” But there were still lounges and restaurants that were reserved for the high rollers.

And the divide went beyond the price of the accommodation.

In the book Steamship Travel in the Interwar Years, Tourist and Third Class, authors Lorraine Coons and Alexander Varias describe an alleged effort of travel writer Ludwig Bemelmans to buy a ticket for a crossing in third class to see how it compared to the luxuries of first class.

He’d crossed in a first class suite de grande luxe on the Normandie, but told his booking agent he wanted to return in third class to find out “how it is down there.” The agent recoiled in horror, replying:

“Non, non, mais non, Monsieur Bemelmans, c’est ne va pas! Victor Hugo did not become a hunchback in order to write about Notre Dame de Paris.”

There’s considerably more comfort these days, because ships are purposely built for cruising.

In a 1927 ad for Caribbean cruises, Cunard promised that in warm climes, “your cabin has cool English chintzes, deep chairs and a cool breeze from the punkah (an adjustable-louver on the porthole).” No air conditioning, in other words.

A cruise ship couldn’t sail anywhere any more without climate control throughout and a majority of accommodations on most new ships feature balconies.

There’s more choice than ever, with a dozen ships doing world cruises in 2017 and 2018. They include the first world circuit in six years for Regent Seven Seas Cruises and three separate world itineraries for Cunard Line. That’s in addition to extended voyages on other ships around the Caribbean and South America.

Another difference between yesteryear and now is that you can get home from anywhere in the world in a day by air. If you don’t have the time or the spare cash to do the whole world in one trip this year, you can book a segment and join on other parts of the journey in following years until you’ve notched up a circuit of the entire globe.

For the price, or the convenience, there’s never been a better time to see the world by ship.

Story by Wallace Immen for The Cruisington Times