Imagine squeezing into a shipping container 12 feet wide and 40 feet long that’s packed with supplies and gear.

Imagine being sealed inside for the next six months with someone you don’t love, practically rubbing shoulders 24/7–except for occasional visits to a little closet that serves as the privy.

It might take the edge off the excitement of being a pioneer in space, unless you’ve got the right stuff.

Cosmonaut Alexander Laveykin is a guy who had it. He came away from six months in space aboard Russia’s Mir space station still on speaking terms with his crewmate. It didn’t always turn out that way.

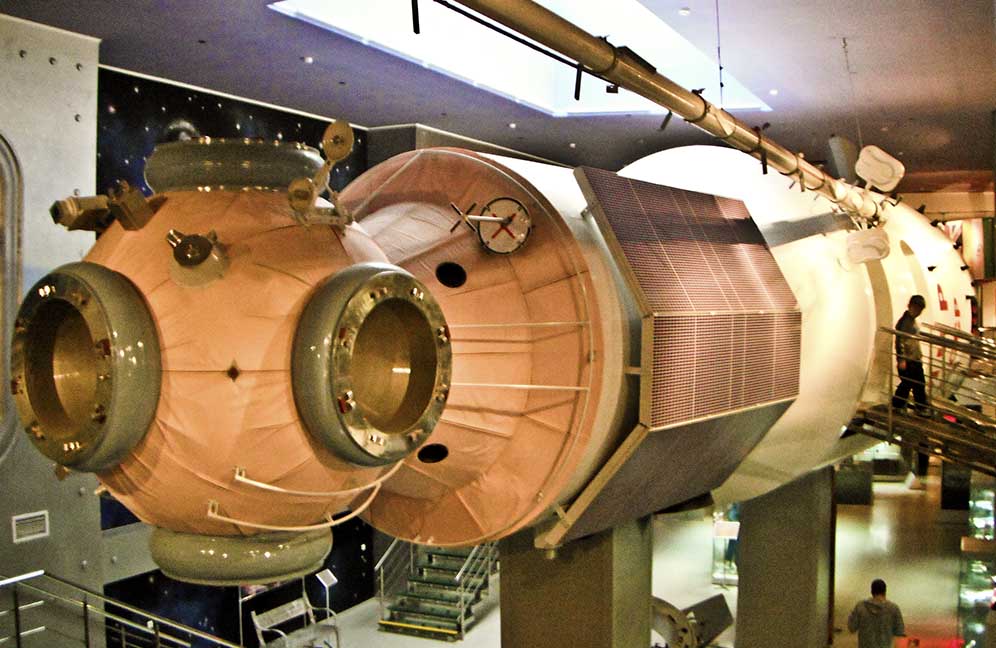

The claustrophobia of life in space was clear as passengers on a shore excursion from Scenic Cruises’ Scenic Tsar got a walk- through of a mock-up of the station at Moscow’s Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics. The main module resembled nothing more than a big can and while empty it was only roomy enough for three or four people at a time. We could only imagine it packed with months’ worth of supplies and experiments on board.

I couldn’t envision spending spending a day here, let alone six months as Mr. Laveykin, now the director of the museum did in 1987. Here’s how he looked then:

His challenges were never-ending. Equipment malfunctions required emergency repairs. The food was freeze dried and bland. The only privacy was during bathroom breaks, where cosmonauts had to squat over funnels that made sure nothing escaped into the gravity-less interior of the ship.

In a special event arranged by Scenic Cruises for passengers of the Scenic Tsar in Moscow we got a chance to sit down and ask questions and relive the then top-secret mission he served on.

I was a correspondent covering the U.S. space shuttle program at NASA’s space centers in the 1980s and I immediately recognized the room we were ushered into as a space center press briefing auditorium. Every seat had a microphone and we were free to ask any question we had about the mission or the space program.

Mir, which is Russian can mean peace or the world was designed to be Russia’s eye in space. The core module had been lifted into orbit in February of 1986 and had short visits by cosmonauts transferring equipment from the earlier Salyut 7 space station which was being decommissioned.

Mr. Laveykin and flight engineer Yuri Viktorovich Romanenko had trained for more than two years in airplanes that simulate weightlessness and isolation chambers designed to simulate the loneliness of long distance astronauts.

But let’s let Comrade Laveykin tell the story.

What was the mission?

We lifted off in February of 1987 as Mission EO-2.

Every time I step inside the model of Mir, my head comes around to that time when I arrived on a Soyuz launch from the Baikonur Cosmodrome with Yuri Romanenko. There was a lot of work to be done because when we arrived, Mir had been unmanned and there were many things put in operation.

We were planning experiments on geology of Earth, looking for gas and oil fields, and in astronomy, observing black holes. There were medical experiments and some practical things like searching for big areas of fish and plankton in the oceans. Yellow patches on the water indicate plankton blooms and those are areas where large schools of fish feed. We were to connect to fishing fleets by radio to tell them where to go. But everywhere the Russian fishing boats went, the Japanese fishing fleet always followed them.

How did you feel on your walks in space?

The highlights of the trip were three space walks. The first was an emergency and I didn’t have much time to do anything but concentrate on the problem. (A second section of the Mir had been sent up unmanned and had to be connected to the first part but there was something preventing docking. The module, named Kvant, needed to be bolted in place or the ship would be unstable and could be damaged as the modules bumped together.)

For hours floating in space I didn’ t even have a chance to look at Earth, I didn’t have any other emotion but to fix the problem. A piece of debris had jammed between the connectors and it took more than three hours in space to fix.

(Later reports found it was a plastic bag that was blocking the module’s bolts and preventing a secure connection. The cosmonauts ended up picking off bits of plastic that may still be floating in space today.)

Two other times outside Mir were planned space walks to replace batteries and check the craft and they provided time to look at Earth. It was beautiful. We had a feeling of awe and it was an incredible feeling floating in space.

The perception of earth from space is incredibly clear and colorful. We were able to see entire continents. Areas that look like green swamp were Latin America and South America. The United States looked like it was covered by a tight network of roads. Western Europe has cities that look like dots with green fields in between.

How do you get along with someone in such close quarters for six months?

It’s very difficult to spend time together for months at a time without a break. Fortunately Cosmonaut Romanenko and I managed to stay good friends and we still visit each other today. But that hasn’t been the case with some other former cosmonaut teams. (Records show that on at least one Mir mission after long months together, a cosmonaut team stopped speaking with each other and would only communicate with controllers on Earth).

Scientists are now studying how to improve the psychological ability of people to spend enforced time together. Being together in a tiny room with no chance for privacy is most difficult. On a flight to Mars people might have to be with each other in space for 500 days.

Did you suffer any medical problems from being weightless? Is there space lag the way there is jet lag after flights on earth?

During a space flight the bones lose calcium and to prevent that we took calcium tablets through the flight. After I landed, my calcium levels rose back to normal levels with exercise and weight training.

It didn’t have any continuing effect on my energy. Aside from the calcium loss from weightlessness and the exposure to solar radiation, the big issue in space is noise. There is no noise in space outside the spacecraft but a lot of equipment makes the small container very loud and there is no escape from it.

A permanent symptom all the cosmonauts have is a hearing loss. My wife always complains that she’s told me things and I don’t remember hearing them. The problem with hearing is, unfortunately, forever.

How did you get back to Earth?

I came back on board a capsule that parachuted to Earth. We landed in Kyrgyzstan in the zone that was planned and we were picked up quickly. That didn’t happen all the time. Some other crews that parachuted back and went off course were sometimes lost for a few hours and in one case for two days.

After my return to the space program I was offered a job connected with the Buran space shuttle program (which was the Russian equivalent of the U.S. space shuttle) but Gorbachev closed the program and I got the job to plan a museum of space craft.

Are you sad that the space program has been reduced?

Yes, it is sad that the cost of space exploration has cut back plans for human exploration of the moon and planets. We should not expect space exploration to turn an immediate profit. Nevertheless humans should continue space exploration because we need the knowledge we can gain. There are threats of global warming and there are risks of an asteroid hitting the Earth. Have you seen the Bruce Willis meteorite movie (the 1998 film Armageddon)? That’s a real scenario.

The continuing story:

After 125 people had visited it in space over 15 years, Mir was finally abandoned. In 2001 it was remotely fired out of orbit and its pieces fell harmlessly into the south Pacific ocean.

Today Russians are part of the teams that man the International Space Station and some of the things learned on the Mir missions have allowed them to improve on life in space.