A brochure welcoming visitors to town asks:

San Juan del Sur: Can you believe it was once a sleepy fishing village?

Yes I can believe it. It still is.

But at least there’s an actual dock for Star Flyer’s tenders to tie up to on our port stop in Nicaragua.

That’s an advantage because Star Clippers’ description of this tour warned we’d have to be prepared for a wet landing on the beach. So at least we didn’t have sand in our shoes during the day trip to Granada, one of Central America’s best preserved colonial towns.

But it was one of several lessons we’d get that in Nicaragua things are not always what you expect.

The fishing village of San Juan might have been a different place today if a decision made more than a century ago to build a shipping canal across Central America had chosen Nicaragua rather than Panama, our guide Enrique explained as we boarded our bus.

The reasons the canal didn’t get built here will make a story in itself. For now, let’s hit the road to the bigger city of Granada.

Immediately it’s clear that the country has lagged far behind neighboring Costa Rica. There are still ox carts along the roads toting goods to market. Most homes are still tin-roofed colonial clapboard wood bungalows painted in blues, yellows and greens.

And in contrast to eco-aware Costa Rica where people never seem to litter the highways and make recycling a religion, Nicaraguans seem to think of roadways and fields as convenient places to dispose of just about anything from plastic bags to kitchen sinks.

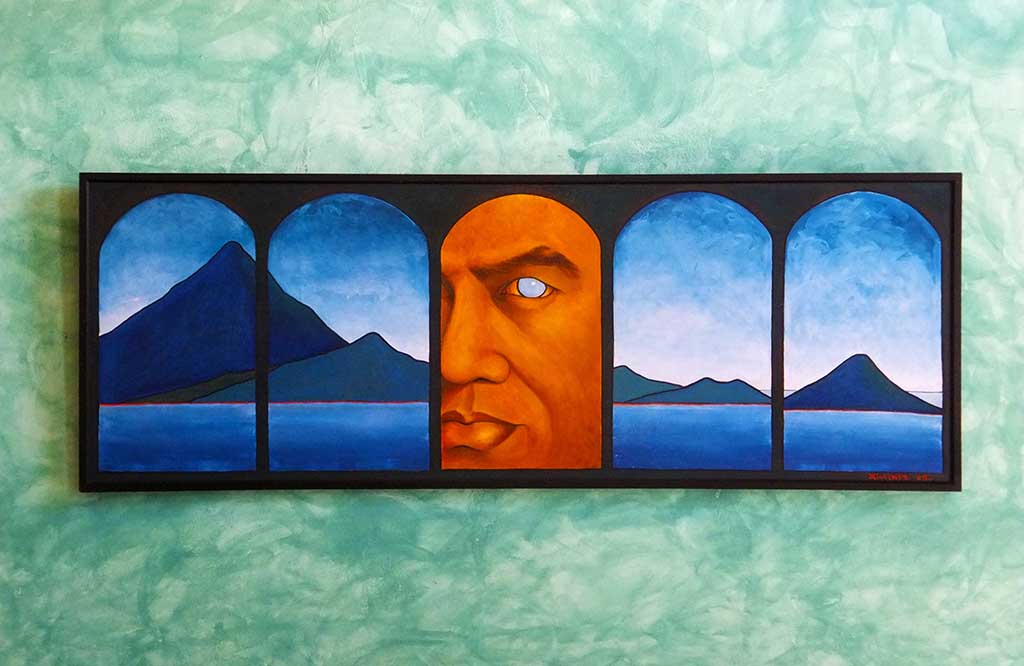

Another constant visual distraction along the roads are giant billboards bearing huge photos of Nicaragua’s Presidente Daniel Ortega, along with slogans promising socialist solidarity and more victories to come.

Yes, he’s the same guy who back in the 1970s was part of the Sandinista junta that defeated Anastasio Somoza Debayle’s forces after a long and bloody civil war. He used to wear military uniforms and heavy eyeglasses. Now he wears designer suits and contact lenses, Enrique quips. He still thinks of himself as a revolutionary even though he’s been running the country as elected president —with a few breaks when he lost elections– since 1984.

There is an opposition party who can try again in 2017, Enrique tells us—making a point as candidly as he can that not everyone is entirely happy with their lot in the new old Nicaragua.

An entire generation of people between ages of 20 and 40 left Nicaragua during and after the civil war and the country is still recovering, he explains. Many Nicaraguan workers still have to migrate to Costa Rica to find work. “We had a revolution and a civil war and for the past 25 years we’ve have had a slow economy, but the people have learned to be resilient and optimistic and welcoming.

We’re definitely welcomed. As an official tour arranged by a local travel agency, our bus is cleared to drive right through check points on the highway. The inspection stations have a state of siege feel as armed soldiers stop and search trucks and cars. It’s explained that there’s a crackdown on drug runners. They use this road, that’s part of the Pan American Highway system that runs more than 20,000 miles from South America through Mexico and the United States.

It’s a pretty drive, with families of large black howler monkeys and white faced capuchin monkeys in trees and ox teams in fields and trees bedecked with pink, yellow and orange flowers.

And soon we’re in Granada, founded in 1523 and laid out in the rectangular grid pattern with a big central square typical of Spanish cities of its time .

The first stop in Granada is its mission whose facade goes back to the earliest days, but is a much more modern structure behind and today is mostly as a museum with the attraction of restrooms that have modern plumbing.

Then it’s a walking tour of the colonial streets whose buildings are painted in bright tropical blues, pinks and greens. Vendors offer big bags of cashews, which are the local produce.

It’s lunch time and Enrique points to the Hotel Dario that faces Parque Central, Granada’s big central park. Today we’ll have lunch at the El Tranvia restaurant that faces the park, Enrique says.

And with a straight face, he adds: “Today’s menu will be a choice of armadillo or road kill. We’ve picked up some nice things the way.”

That’s a joke folks, but it takes a moment to sink in.

The courtyard restaurant’s buffet thankfully doesn’t have any armadillo or boa on the menu. The chefs pepare a fusion of Caribbean and Latin foods and I found the jerk chicken extremely tasty.

I wash lunch down with a Macua or two. That’s Nicaragua’s national cocktail and made from guava and orange juices and copious amounts of the local Ron de Flor rum

They hit the spot here and would probably go well with the menus at some other restaurants in town whose menus may also include iguana (chicken of the tree), boa and armadillo. Everywhere you go you’ll find corn tortillas, beans and rice and potato or plantain are the staples for breakfast or lunch.

We leave the restaurant for a leisurely stroll around the square with its cab rank of brightly painted carriages drawn by teams of horses ornately decked out in ribbons.

Maybe it’s the rum affecting me, but I came away very impressed at how bustling and how well-restored much of Granada appears to be and how welcoming the people really are.

From Granada we’re heading out to the country to see Nicaragua’s claim to fame and infamy: its volcanoes. We were about to see the gates of Hell.

No need to volunteer as a sacrifice. Just check out my next story on Nicaragua.