It’s an underwater sculpture garden, with what look like concrete beehives, archways and even statues that are covered with glimmering growing things on the ocean bottom. Brightly colored fish swim in clusters and eyes peek out of nooks and crannies.

On a Mexican cruise, I’m snorkeling very carefully through the scene as experts plant tiny creatures almost invisible to the naked eye that they hope will be able to multiply and build imposing coral condos. It’s part of what scientists hope will be a way to restore endangered coral reefs around the world.

Our guide on this expedition from Oceania Cruises’ flagship Riviera docked in Cozumel is the inspirational German Mendez, who has devoted his life to mastering the art of coral farming as part of the Cozumel Coral Reef Restoration Program.

When Mendez first moved to Cozumel 30 years ago, the healthy coral reefs along the coast formed a beautiful bulwark against storm surges and were the breeding ground to a multitude of fish.

He was a vocal opponent of a plan to develop cruise ship port inside an existing marine protected area, but he met defeat as cruise docks and development of a complex on the shore were approved by the Cozumel government in 1994.

Mendez then decided to get a master’s degree in marine biology at Florida State University. To his dismay, on his return just four years later Cozumel’s reef ecology was already in serious decline. Surveying the reefs near the completed port, he estimated more than half of the coral had died while he was away. Now, he’s devoted his life to finding ways to restore endangered reefs along Latin America and in other parts of the world.

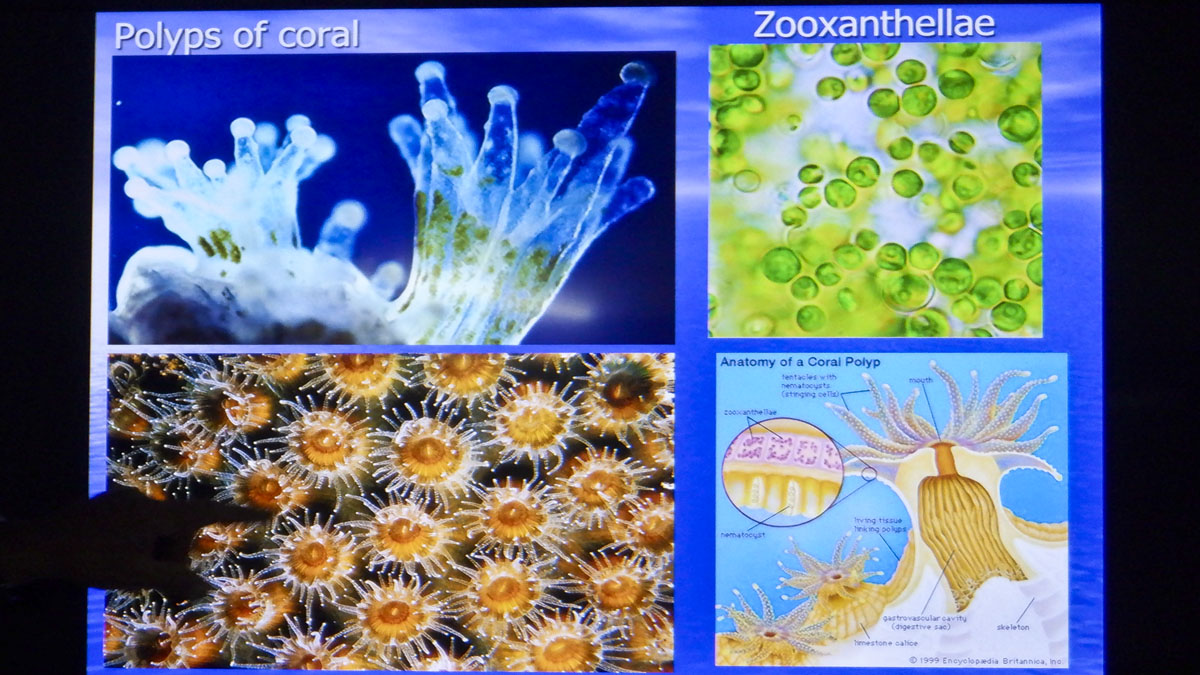

The tour begins with a presentation in the laboratory, where tiny coral polyps are hatched in tanks and encouraged to attach themselves to jack-shaped concrete castings that can literally be tossed from row boats and lodge themselves firmly on the bottom as the foundations of a new coral heads. In the lab tanks, they’re fed with a fish food nicknamed reef chili.

The polyps multiply quickly and begin to form the calcium shells that we recognize as coral. As they reproduce, new generations attach to the existing coral and form clusters that build into shapes that look like hands, antlers or even brains, depending on the species.

Just one per cent of the ocean floor is covered by reefs, but they are essential not only to protecting shorelines from storm damage but also as the breeding grounds of fish and other sea creatures, we’re told. The reef running from Central America to Florida is the world’s second-longest barrier reef, after the Great Barrier Reef in Australia

Then it’s time to dive in. The lab is located at Sand Dollar Sports, a popular scuba and snorkel center in Cozumel. They’ve got the mask, snorkel and fins you need for the tour of an experimental farm testing different structures that can encourage growth of different kinds of coral.

We’re encouraged to wear a reef-safe organic sunblock. That’s because the oxybenzone, PABA, benzophenone, titanium dioxide and zinc oxide commonly used in sunblocks can be toxic to coral colonies. (When snorkeling under the direct sun in Mexico, a t-shirt is also a good protection against a sunburnt back.)

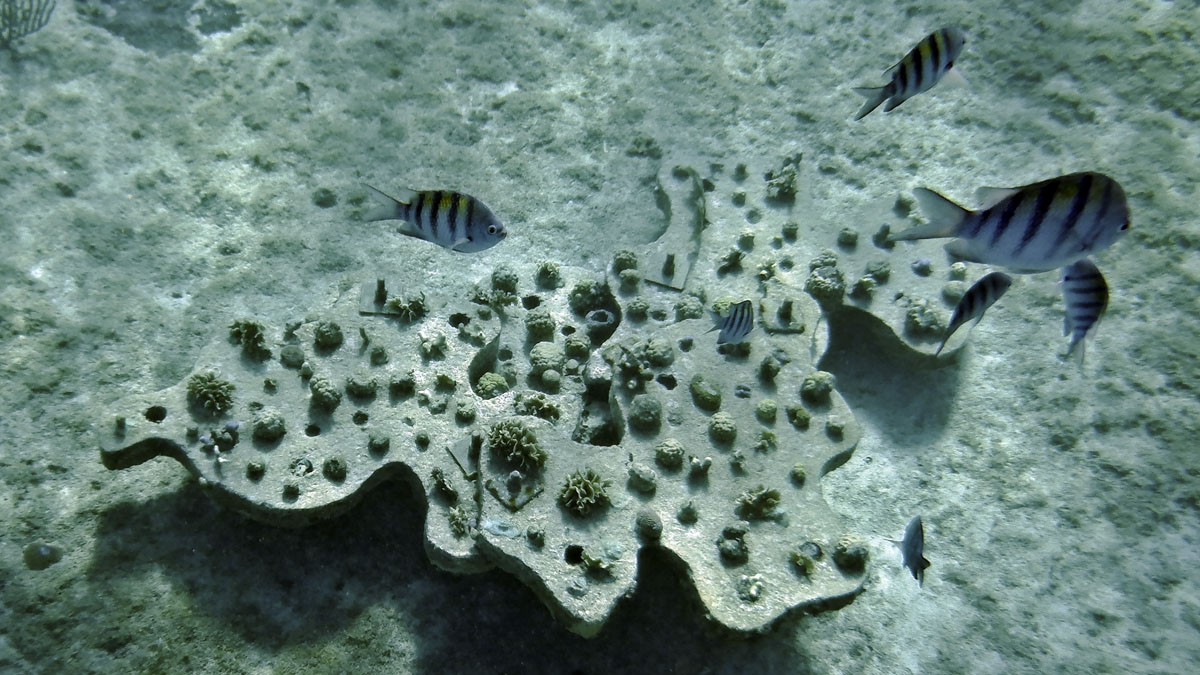

Only a five-minute swim offshore, structures in the shallow sandy bottom demonstrate that the reef-building process can happen quickly under the right conditions. Different types of corals are attached to various surfaces, each identified by a number, to see where they grow best. The reef structures are already becoming the habitats of a wide range of fish.

In this shallow area so close to the cruise port, daily housekeeping of the coral nursery is essential in order to prevent buildup of sediment stirred up by ships that have made Cozumel one of the most popular cruise destinations in the world.

Other threats are algae blooms that deplete oxygen in the water, most famously the red tide which has devastated reefs along Florida. Ironically, a program by resorts in the 1980s to eliminate sea urchins, whose spines could cut tourists’ feet, removed one of the better algae removal systems in the oceans and now there’s a program to reintroduce urchins, Mendez says.

Back on land, our tour group had a new respect for the complex life of a reef and how quickly the ecology can be endangered.

“I have to start in my backyard. And if I start in my backyard maybe I can make an example and other people want to do it in their backyard too,” Mendez says. “Let’s not love the reef to death, but learn about it.”